By Alexia Robinson

•

September 26, 2025

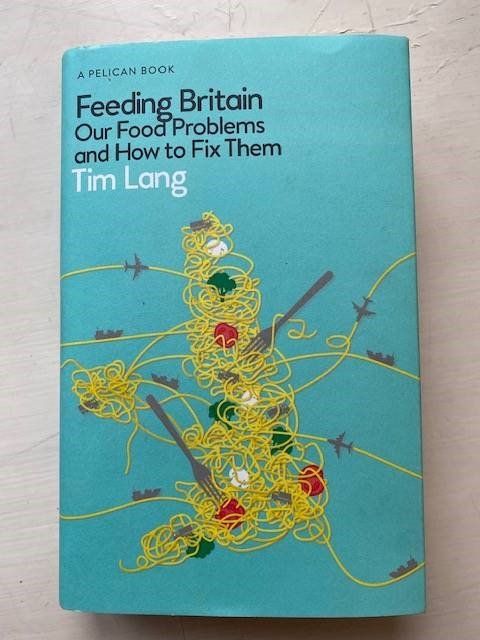

The UK’s largest annual celebration of homegrown food and the farmers who produce it, returns from 26 September to 12 October. The nation comes together for British Food Fortnight, for the 24 th year, with founder and CEO, Alexia Robinson, saying: “This year’s theme shines a spotlight on food’s deep-rooted connections with each of us – the bond that sustains the nation, physically, culturally, and economically. “Against a backdrop of global uncertainty, political pressures, and a challenging market, ensuring Britain’s food security is our number one priority.” At the heart of British Food Fortnight is a rallying call to back British farmers and celebrate the quality, diversity, and provenance of our food. Leading industry figures and organisations are uniting to support the campaign. Nation Farmers Union president, Tom Bradshaw says: “This British Food Fortnight comes on the back of a very hard two years for many farmers and growers. Public support means the world to those out in all weathers producing great British food for the nation. This fortnight is a great chance to celebrate all they do, so please show your support by trying to buy British wherever you can.” It is a sentiment echoed by Shadow Farming Minister, Robbie Moore MP, who says: “From the family farms that have been part of our countryside for generations to our young farmers bringing fresh ideas into the industry, British farming is the backbone of our rural economy. This year’s Food Fortnight celebrations are bigger than ever and I would encourage everyone to use this moment to show their support!” A true community movement, British Food Fortnight stretches from field to fork, reaching into every corner of the UK. For the first time celebrations are planned across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. From city authorities to remote rural village halls, from the nation’s classrooms to its care homes, to universities and hospitals, everyone is united by one thing – putting British food centre stage. From giant puddings, floating food festivals, street food cookery workshops, bakery tours to farm visits, anyone can join in the fun. On the high street, the newly launched Community Champion of Change competition, is running in collaboration with lead retail partner, Morrisons, celebrating individuals and groups who are making a difference in backing British food. At a grassroots level, farmers have expressed their support of this vital campaign and encourage the public to take part. As Gloucestershire pig farmer, Anna Longthorp explains: “There is only one person with more power than supermarkets and successive governments, and that is you, the consumer; vote with your hard-earned cash and buy British.” David Webster, chief executive of LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) says: “British Food Fortnight is a powerful reminder of the incredible contribution our farmers make – not only in producing high-quality, sustainable food, but also in caring for our environment and supporting rural communities.” Reaching a crescendo The celebrations culminate with the Harvest Torch, which has travelled from Southwark Cathedral to Suffolk where it has been paraded at agricultural shows all summer culminating in a special Harvest Service at St Edmundsbury Cathedral in Bury St Edmunds on Sunday 5th October, the middle weekend of British Food Fortnight. From there it will travel to London for the National Harvest Service at Westminster Abbey the week after the national food celebrations, on World Food Day, where it will be carried by the President of the NFU and lead the Offertory Procession. This finale brings together a partnership between Love British Food with The Trussell Trust, The Felix Project, the Coronation Food Project and City Harvest, highlighting the importance of making good food accessible to all. Get involved “We are incredibly grateful for the support from all our partners and Food Heroes who help us amplify the voices of British farmers and ensure British Food Fortnight 2025 is a resounding success in promoting local, sustainable food,” adds Alexia. Let’s come together to grow, cook, and champion British food, supporting our farmers every step of the way. To discover how to take part and find local events, visit www.lovebritishfood.co.uk or follow @LoveBritishFood on social media. Supporters from across the supply chain have shared their commitment to British Food Fortnight: “From hospitals to hospitality, British food creates some fantastic dishes and it’s only right that we celebrate the amazing contribution our farmers and growers make,” James Armitage, marketing director, Fresh Direct. “Choosing British strengthens supply chains, supports rural jobs, and promotes sustainable farming. For organisations, it’s a chance to show real commitment to provenance and resilience.” Philip Rayner, co-founder and MD, Glebe Farm Foods “School meals play a vital role in shaping children’s health and learning, and British Food Fortnight is the perfect opportunity to showcase the importance of fresh, local, and seasonal produce on the plates of our young people. By supporting British farmers, we not only invest in our children’s wellbeing but also strengthen our communities and food system for the future." Derek Wright, catering service manager, Blackpool Catering Services “We’re proud to champion British Food Fortnight by showcasing the best of local produce. Supporting British farmers and suppliers isn’t just about great taste — it’s about sustainability, quality, and celebrating the food heritage that brings communities together.” Caroline Morgan, Local Food Links, Dorset "Supporting British farming means supporting nature, rural economies, and the future of local produce. British Food Fortnight is an opportunity to showcase the innovation and passion at the heart of our industry.” Sarah Haire, Dunbia. “I’m delighted for NSA to join lots of other farming and food organisations in being part of British Food Fortnight. It’s really important to reflect on just how fortunate we are to have such an abundance of high quality food and drink, produced here in Britain with care and a lot of hard work by farmers and many others throughout our supply chain. ” Phil Stocker, chief executive of the National Sheep Association Farmers from across the UK have also added the voices: “British farmers and growers are resilient, hardworking, innovative and deliver some of the highest quality and best tasting food in the world. British Food Fortnight is a celebration of all our hard work!” Alison Capper, Worcestershire farmer and executive chair of British Apples & Pears “British food fortnight showcases the safe, ethical and sustainable food produced by British farmers - supporting British farmers, helps sustain our food security, rural communities and countryside.” Holly Atkinson, dairy farmer, Devon “British Food Fortnight is a great opportunity to support farmers, to help them produce healthy, nutritious food, while at the same time benefiting nature. When nature thrives, so does farming, and when farming thrives, so does the country.” James Robinson, Strickley Farm, Cumbria “Supporting British farmers means backing the people who care for our land, produce high-quality food, and steward our countryside for future generations, British Food Fortnight is the perfect moment to celebrate that.” Sophie Gregory, dairy farmer, Devon